Treed mountain lion in Montana. Photo credit: 41 Digital

California mountain lion distribution. Source: naturemappingfoundation.org

Photo credit: 41 Digital

Daniel Richards' Idaho mountain lion. Photo credit: Western Outdoor News

I awoke abruptly to the harsh sound of my cell phone alarm. My neck was stiff from sleeping in the front seat of my pickup and I sat up, rubbing the sleep from my eyes. As I opened the door, a rush of cool air rolled in and I was awake; the mere three hours of sleep seemed no more than a few seconds long. Jason, Shane and I had arrived at the trailhead late the previous night after a long day at work and a two-hour drive. I woke the others and downed the half empty cup of now cold coffee that was still in the cupholder from last night’s drive. We all made one last check of our gear and donned our heavy packs; we planned on spending the next five days in the backcountry.

Headlamps glowing, we started up the trail in darkness. Not long into our trek, Shane realized that he had forgotten to change the batteries in his lamp. He turned back to retrieve batteries from the truck and Jason and I pressed on, knowing that he would eventually catch up. It was the Friday before the opener of California’s archery season and we were anxious to set up camp and start looking for deer. The timber began to glow with the rising sun and soon the headlamps were no longer necessary. We continued to grind uphill, anxious to reach the top. But as I looked ahead, I caught movement on the trail.

The hair on the back of my neck stood up and I felt as though I was seeing a ghost. Coming straight down the trail at a mere 40 yards was a mountain lion. He stopped for a moment; our eyes met and I froze. The cat looked almost as surprised as I was and silently tucked into the timber to my left. I watched in awe as he moved to cover behind some deadfall and sat down. I turned to Jason, who was a few steps behind me, and told him that there was a cat 40 yards away, sitting and watching us. He scrambled to get his camera and tried to shoot some video. Almost as quickly and silently as he appeared, he was gone. I caught another glimpse of him as he slinked along parallel to the trail and out of sight. It wasn’t until I could no longer see him that fear set in.

Was he doubling back to flank our back trail? Quickly, my mind went to Shane. I knew that he would be catching up to us soon so we cautiously doubled back to a switchback. I yelled to Shane and heard him respond; he was not that far away. Suddenly, my senses heightened. The hair on my neck stood up again and my heart started to race. I scanned the woods where I had last seen the mountain lion and turned up nothing. I turned to my left and there he was. Now only 20 yards away, the cat was crouched, as if he was stalking me, and poised to chase. I wished that I was carrying my pistol, but it is illegal to carry a firearm while hunting during the archery only season in California.

Immediately, I began to yell, clanging my trekking poles together and kicking rocks. The thought of removing my pack and grabbing my bow only made me feel more vulnerable. Fortunately, the cat seceded to my challenge and turned, quickly disappearing again. I stood in the trail, shaking with adrenaline; I couldn’t help but feel lucky that the cat had not called my bluff.

In 1990, a state initiative was passed that made the hunting of mountain lions illegal in California. Proposition 117, dubbed the "California Wildlife Protection Act," was posed as a conservation act that acquired habitat for deer, mountain lions and endangered species. It promised $30 million to be allocated for the preservation of habitat over a 30 year period. On the surface, this is an initiative that even hunters could get behind; however, details of the proposition also would place mountain lions on the "specially protected species list," and the allocation of funds would be taken from both the general state fund as well as the "unallocated account" of the state. In short, this new $30 million fund, called the "Habitat Conservation Fund," would be covered by taxpayers.

For those unfamiliar with California state initiatives, they are essentially propositions approved by state legislature for a public vote. California, being a predominantly liberal state, passed the initiative that leaned heavily on verbiage of conservation of habitat with a 52.42% vote. This placed the mountain lion on the specially protected species list, which would require at 4/5 vote of legislature, or a majority vote of the people, to overturn.

According to the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) website, "this status and other statutes prohibit the CDFW from recommending a hunting season for lions and it is illegal to take, injure, possess, transport, import, or sell any mountain lion or part of a mountain lion." This includes any lions taken legally in another state. Even lions mounted by a taxidermist are illegal to transport or possess in California. This initiative was backed by the Mountain Lion Foundation (MLF), an activist group that believes that mountain lions are in peril and that "our nation is on the verge of destroying this apex species upon which whole ecosystems depend." They also state that hunting of mountain lions is "morally unjustified."

Conversely, the CDFW website states that "mountain lions are not threatened nor endangered in California. In fact, the lion population is relatively high in California and their numbers appear to be stable. Mountain lions are legally classified as “specially protected species,” [however] “this has nothing to do with their relative abundance and does not imply that they are rare.”" Herein lies the problem: activist groups such as the MLF, who have a special interest of "protecting" wildlife, are preying on the liberal majority's emotion to raise money and using said funds to write state law.

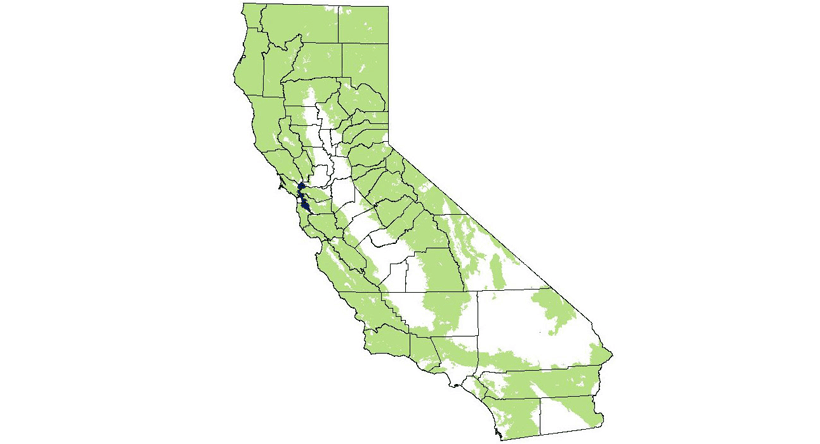

# of mountain lions in California

In doing so, they are handcuffing agencies such as the CDFW, who employ biologists and experts to make decisions on how to manage wildlife effectively. Because of the law that the MLF brought into existence, these biologists and experts are not allowed to apply management strategies to lions. Instead, this decision is left to the emotionally driven and generally ignorant general public. What is extremely comical is a statement gleaned from the MLF’s mission statement that says, "Governments should base decisions upon truthful science, valid data, and the highest common good." The decision to place the mountain lion on the specially protected species list is based on none of these principles.

California mountain lion distribution. Source: naturemappingfoundation.org

In 1997, proposition 197 proposed that mountain lions' status as a specially protected species be repealed. It suggested that CDFW "manage mountain lions as it manages mammals that are not rare, endangered [or] threatened," and "implement mountain lion management plan that promotes health, safety, livestock, [and] property protection." In addition, 197 proposed that state legislature change laws about mountain lions with a simple majority vote, rather than a 4/5 vote. Proposition 197 was defeated in a public vote by 58.12%.

In 1999, the Sierra (California) Bighorn Sheep population plummeted to approximately 100 animals and was added to the Federal List of Threatened and Endangered Species List. This designation provoked the 4/5 vote in state legislature to amend the wildlife protection act and allow the management of mountain lions that posed an imminent threat to the dwindling sheep herd. CDFW collared and tracked cats and dispatched those that posed a threat. This cost taxpayers over $250,000. This move was combatted by the MLF that published such statements as, "the management of mountain lions over most of their range continues to be dictated by hunting-driven management philosophies rather than by conservation."

Special interest groups like the MLF and the Humane Society of the US (HSUS) oppose hunting of any kind, are well organized and well funded. They oppose hunting on the basis of morality and emotion rather than on science. It is well documented that responsible hunting and wildlife management is the most effective conservation model. Where all of the laws and initiatives backed by animal rights activists require taxpayers to foot the bill of conservation efforts, hunting generates revenue to pay for research and habitat conservation. Had the mountain lion not been considered a protected species, CDFW could have approved a depredation hunt on the population of cats that threatened the bighorn. This would have generated revenue via tag sales and cut the cost of paying CDFW personnel to collar and eradicate the problem cats. While activist groups raise money to pass laws that prevent hunting and take the decision making power for wildlife management out of the hands of biologists and state agencies, hunters generate millions in revenue each year for wildlife conservation.

According to a study in the Journal of Wildlife Management, 68% of predator caused mortality in California mule deer is the handiwork of mountain lions. With conservative population estimates of mountain lions in California between 4,000 to 6,000 and the constant infringement of human expansion on habitat, the unchecked population of mountain lions pose a threat to ungulates as well as livestock. The MLF would argue that mountain lion populations are naturally controlled by two main factors: first, that they defend a vast home range and that reproduction rates are limited; second, lion populations are naturally balanced proportionately to prey populations and only feed on the weak. Research has yielded conflicting results. According to the June 1989 issue of Forest Research West, a USFS publication, "mountain lions appear to be controlling an already depressed deer herd, and they are apparently not benefiting the population by taking only the weak and old. The density of the lion population is not limited by the need for exclusive territories, and reproduction is continuing within this high-density population." Also, "Livestock losses to mountain lions have become a serious concern of this team. The number of permits to take mountain lions that are killing livestock reached an all-time high in 1988, with 145 issued and 62 lions taken. Neal, Steger, and Bertram (from the study), expect livestock predation to continue at a high level or even increase, and deer to continue to decline in all but the most favorable years." This study was conducted in the late 1980s. The initiative that made mountain lion hunting illegal was passed in 1990.

Another example of the unchecked influence of animal rights activists in California legislature is the case of Daniel Richards, who was ousted from his position as president of the California Fish and Game Commission. Richards came under fire for legally taking a mountain lion on a hunting trip in Idaho. This was all the HSUS needed to boot Richards, a NRA lifetime member and political conservative, who represented sportsmen on the Commission. Petitions were signed and propaganda was spread, resulting in the legislature voting him out as president. The reason given was that he showed poor judgement and did not honor the voters of California who have chosen to protect mountain lions. This was not California's cat, but Richards was an obstacle to the agenda of the activist groups and his legal take of a mountain lion in Idaho was all that was needed to remove him.

It is prudent to note that predation is not the only issue that declining deer herds face. Fragmentation as well as the loss of habitat are still leading factors; however, the deer herd in California is in a steady decline as the population of predators increase. The ban on hunting mountain lions has taken the decision making power out of the hands of experts on wildlife management and handed it over to the gullible and uninformed public while mountain lion populations continue to grow. In their effort to "effectively ban all hunting," the HSUS and other animal rights groups are working tirelessly to raise funds and implement legislature. This not only alienates sportsmen, but puts other species, including domestic pets and livestock, at risk.

The opposition to sportsmen in California is well organized and well funded. Their time and effort is spent trying to end hunting in California. The case of the mountain lion is a major victory of the special interest groups listed above. When wildlife management is placed in the hands of "environmentalist" organizations and the general voting public, sportsmen and wildlife lose. The only way to combat this trend is for sportsmen to unite in a concerted effort to preserve and restore our heritage. Make no mistake: there are people out there whose goal is to prevent you from hunting and they are gaining ground in our state. We must meet them with equal tenacity if we stand a chance to preserve our wildlife and the heritage that we hold most dear.