Checking cam timing holes on Mathews VXR 31.5.

Top and bottom cams are in time.

Rest | Move rest right |

|---|---|

Cam(s) | Move cam(s) left orshort left yoke |

Arrow | Use stiffer arrow ordecrease point weight |

Cable guard | Move cable guardtoward arrow |

Rest | Cam(s) | Arrow | Cable guard |

|---|---|---|---|

Move rest right | Move cam(s) left orshort left yoke | Use stiffer arrow ordecrease point weight | Move cable guardtoward arrow |

Rest | Move rest left |

|---|---|

Cam(s) | Move cam(s) right orshorten right yoke |

Arrow | Use weaker arrow orincrease point weight |

Cable guard | Move cable guardaway from arrow |

Rest | Cam(s) | Arrow | Cable guard |

|---|---|---|---|

Move rest left | Move cam(s) right orshorten right yoke | Use weaker arrow orincrease point weight | Move cable guardaway from arrow |

Rest | Move rest up |

|---|---|

Nock point | Move nockpoint down |

Cam(s) | Twist cable fortop cam |

Cable guard | Take a 1/4" turn outof top limb bolt |

Rest | Nock point | Cam(s) | Cable guard |

|---|---|---|---|

Move rest up | Move nockpoint down | Twist cable fortop cam | Take a 1/4" turn outof top limb bolt |

Rest | Move rest down |

|---|---|

Cam(s) | Move nockpoint up |

Arrow | Twist cable forbottom cam |

Cable guard | Take a 1/4" turn outof bottom limb bolt |

Rest | Cam(s) | Arrow | Cable guard |

|---|---|---|---|

Move rest down | Move nockpoint up | Twist cable forbottom cam | Take a 1/4" turn outof bottom limb bolt |

| Rest |

|---|---|

Bare shaft left | Move rest left |

Bare shaft right | Move rest right |

Bare shaft high | Lower rest |

Bare shaft low | Raise rest |

| Nock point |

Bare shaft left | - |

Bare shaft right | - |

Bare shaft high | Raise knocking point |

Bare shaft low | Lower nocking point |

| Cam(s) |

Bare shaft left | Move cam right |

Bare shaft right | Move cam left |

Bare shaft high | - |

Bare shaft low | - |

| Yokes |

Bare shaft left | Twist right yoke |

Bare shaft right | Twist left yoke |

Bare shaft high | - |

Bare shaft low | - |

| Cam(s) |

Bare shaft left | Move cam right |

Bare shaft right | Move cam left |

Bare shaft high | - |

Bare shaft low | - |

| Cam Timing |

Bare shaft left | - |

Bare shaft right | - |

Bare shaft high | Twist cable bottom cam |

Bare shaft low | Twist cable top cam |

| Arrows |

Bare shaft left | Maybe too stiff |

Bare shaft right | Maybe too weak |

Bare shaft high | - |

Bare shaft low | - |

| Othercause |

Bare shaft left | Draw lengthmaybe too short |

Bare shaft right | Draw lengthmaybe too long |

Bare shaft high | - |

Bare shaft low | - |

| Bare shaft left | Bare shaft right | Bare shaft high | Bare shaft low |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Rest | Move rest left | Move rest right | Lower rest | Raise rest |

Nock point | - | - | Raise knocking point | Lower nocking point |

Cam(s) | Move cam right | Move cam left | - | - |

Yokes | Twist right yoke | Twist left yoke | - | - |

Cam(s) | Move cam right | Move cam left | - | - |

Cam Timing | - | - | Twist cable bottom cam | Twist cable top cam |

Arrows | Maybe too stiff | Maybe too weak | - | - |

Othercause | Draw lengthmaybe too short | Draw lengthmaybe too long | - | - |

Issue | Broadheads hitting left |

|---|---|

Rest fix | Move rest left |

Cam fix | Move cam right |

Issue | Broadheads hitting right |

Rest fix | Move rest right |

Cam fix | Move cam left |

Issue | Broadheads hitting high |

Rest fix | Move rest downor move nock point up |

Cam fix | Twist cable forbottom cam |

Issue | Broadheads hitting low |

Rest fix | Move rest up ormove nock point down |

Cam fix | Twist cable for top cam |

Issue | Rest fix | Cam fix |

|---|---|---|

Broadheads hitting left | Move rest left | Move cam right |

Broadheads hitting right | Move rest right | Move cam left |

Broadheads hitting high | Move rest downor move nock point up | Twist cable forbottom cam |

Broadheads hitting low | Move rest up ormove nock point down | Twist cable for top cam |

| Axle to axle |

|---|---|

Twisting string | Decreases |

Untwisting string | Increases |

Twisting cable | Decreases |

Untwisting cable | Decreases |

| Brace height |

Twisting string | Increases |

Untwisting string | Decreases |

Twisting cable | Increases |

Untwisting cable | Decreases |

| Holding weight |

Twisting string | Increases |

Untwisting string | Decreases |

Twisting cable | Decreases |

Untwisting cable | Increases |

| Draw length |

Twisting string | Decreases |

Untwisting string | Increases |

Twisting cable | Increases |

Untwisting cable | Decreases |

| Twisting string | Untwisting string | Twisting cable | Untwisting cable |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Axle to axle | Decreases | Increases | Decreases | Decreases |

Brace height | Increases | Decreases | Increases | Decreases |

Holding weight | Increases | Decreases | Decreases | Increases |

Draw length | Decreases | Increases | Increases | Decreases |

I hear it often this time of year, “I need to get my bow tuned up” or “I’m having trouble getting my bow to tune.” Generally speaking, tuning a bow might seem mysterious or at least something that can only be done by your local pro shop. While your local pro shop is a great resource to get your bow tuned, tuning a bow is something that every bowhunter should at least understand and, in many cases, do themselves. So let’s talk about what tuning actually means.

For me, my ultimate goal is to deliver a broadhead-tipped arrow to the exact spot I intend it to hit. Specifically, I want it to hit at 20 yards all the way to 80 yards. I want the arrow to enter as straight as possible, cutting efficiently and carrying as much kinetic energy through as it can. I also want the bow to be a little bit forgiving to a slight tweak in my form in a less than perfect situation. I want it to hold well and be accurate. I also want to be able to spend the preseason months practicing with both field and broadhead-tipped arrows. I want them to hit together and I want my practice to build my confidence and confirm that my form and bow and arrow setup are as lethal as I can get them. That is what I consider a well-tuned bow. With that, let’s jump into how to tune a compound bow.

Some suggest that a bow has to “paper tune,” which is a visual indication of what an arrow is doing very quickly after it leaves the bow. Others discard paper tuning altogether and suggest that “bare shaft” tuning is the only way to properly tune. A few other types of tuning methods that are tossed around are “group tuning,” “broadhead tuning,” “walk-back tuning” and, perhaps, even torque tuning although that is addressing a more specific issue. Every method has its fans and its critics. Personally, I like to utilize multiple methods. By doing this, I gain greater confidence in my setup.

Whether you are pulling a brand new bow out of the box or you are starting over and setting your bow up again from scratch, the first thing I like to do is bottom out both the top and bottom limbs. Next, I visually check for cam timing. By cam timing, I mean that both cams are in sync and both roll over at the same time. Well-timed cams allow the draw stops on each cam to contact the cables or limbs at exactly the same time. Many of the newer compound bows have indication marks or holes on the cams that you can look at to see if the cams are timed.

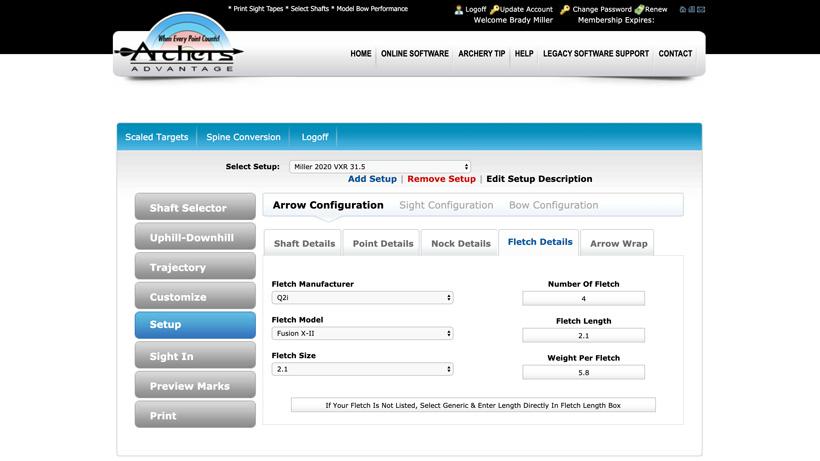

Checking cam timing holes on Mathews VXR 31.5.

For example, my Mathews VXR has a hole on each cam that you can look at to see where the cable is in relation to the cam. Each cable centered visually through those holes tells me that the bow is likely in time. Cam timing is important. If one cam is reaching full rotation before the other, it will result in an arrow that, if receiving more rotation from one cam, results in an arrow that will show either high or low paper tears that you probably won’t be able to work out by moving your rest or nocking point. Long story short: do a quick check visually for cam timing before you even get started.

Top and bottom cams are in time.

Cam rotation can be manipulated by adding or even removing twists from the cables in order to get the draw stops hitting at the same time. If you twist a cable, you are effectively shortening it, thus increasing the distance the draw stop has to rotate to stop. Untwisting does the opposite — it lengthens the cable and reduces the distance of rotation for the draw stop to hit. I always try to utilize twisting cables or strings rather than untwisting. Also, be aware that the twisting and untwisting can have other impacts on draw length and draw weight.

Also at this point, I like to do a quick measure of the axle to axle length and the brace height to see if those measurements meet the manufacturer's recommendations. Axle to axle is measured from the center of the top axle to the center of the bottom axle on the shelf side of the bow. Brace height is measured from the deepest part of the grip to the bow string. If your bow appears to have good cam timing and the brace height and axle to axle are close to factory spec, then my next step is to set a nocking point.

To set a nocking point, my method is to measure the distance between the two axles and set my nocking point so the arrow is centered between that. I then tie in my nocking point. After that, I install my rest and lock it down with my arrow at a 90 degree angle to the string.

Another method is to attach your rest is to put your bow in a bow vise. Use a level and the vise to put your bow in a position that your string is perfectly vertical (i.e. level). Next, use an arrow on your string and adjust your rest height so that the arrow is running through the center of the berger hole (rest attachment hole) and it is 90 degrees running from your leveled string. At that point, tie in your nocking point(s) and secure your rest vertically.

After I have the nocking point tied in, my rest attached and the arrow squared, I set the horizontal location of my rest. I start with my rest at 13/16” from the edge of the riser. I may end up moving that if need be, but that’s a good starting point. For my Mathews bows, that is the magic spot for my rest.

With the nocking point and rest set, I tie in my D-loop. After that, I draw the bow several times to get a feel for the cam timing. A draw board is the best way to check timing, but if you do not have one you can have someone watch your cams as you draw. You can also get a good feel for it yourself by slowing down and drawing your bow repeatedly. Never draw a bow without having an arrow nocked.

Before moving to the next step of actually shooting the bow you have to think about arrow selection and the other accessories you are going to put on your bow.

You will need to shoot an arrow that has the proper spine for your setup. By spine, I mean the stiffness of the arrow. If the arrow is too weakly spined or too stiffly spined for your bow, it will be very tough and likely impossible to tune. Most arrow manufacturers have charts they provide where you can find your draw length and draw weight. The chart will indicate the proper spine for you to shoot.

Another method, which is what I would recommend, is to utilize the “shaft selector” software that is available online through a company called Archers Advantage. The cost is about $10 and, with it, you can build setups and generate an arrow that is perfectly tailored to you.

For example, I can input the model of bow, my draw length and draw weight. Then, I can play with arrow spines, lengths, components and I can create the perfect arrow for my bow. It’s a great product and I highly recommend it.

After you have picked an arrow, I’d suggest that you work on getting your stabilizer(s) and sight attached. Anything on your bow, including your accessories — even your peep sight — is going to impact the tune. I’ve seen guys shoot a bare bow that tuned perfectly and then added a stabilizer setup and they suddenly have a bad paper tear or poor bare shaft results.

Finally, you have your bow set up and are ready to fire a few arrows and start to tune.

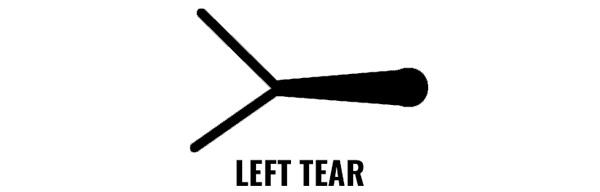

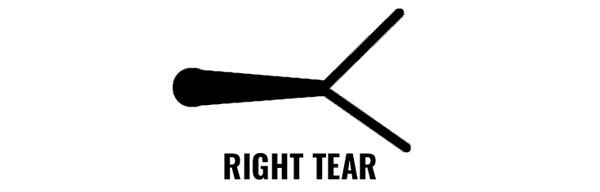

I like to start out by paper tuning. For one, it’s relatively easy to do in a small space and I can do it at home in my equipment room. To paper tune your bow, you’ll need a bow, arrows, a frame that can hold a piece of paper that you can shoot through and a target placed behind it. The goal of paper tuning is to stand approximately 6’ to 8’ from the paper and shoot an arrow through the paper into the target. The resulting “tear” through the paper is a perfectly centered hole. A perfect tear would indicate the arrow is leaving the bow with true flight. In order to get a perfect paper tear, your arrow rest, nocking point, cam timing, grip and arrow spine all have to be correct.

A combo of tears can be fixed by combining methods. For example, a high left tear might be fixed by moving the rest right and up. Generally, I would recommend you start with the easiest adjustment and retest before moving to steps like stiffer or weaker arrows, cam shimming, etc. More information on how to tune a Mathews bow with top hats can be found here.

After paper tuning, bare shaft tuning is my second step in the process. Bare shaft tuning is quite simple, but you have to have relatively good, repeatable shooting form. Start with two or three bare shafts (no fletchings) and two or three regular fletched arrows and shoot them, starting at about 15 to 20 yards. The goal is to have the bare shaft and the fletched arrows hit the exact same point. The bare shaft should enter the target at the same vertical and horizontal plane/angle as the fletched arrows. A well-tuned bow will group those arrows together and they will enter the target exactly the same way.

Similar to the paper tuning method, your options for getting good bare shaft flight are to move the rest, the nocking point, the cam(s) left or right, adjust the left or right yoke, adjust the cam timing or make changes to your arrow setup.

As you begin to tune, make changes in small increments. It also helps to record the changes you make and monitor the results. It may take days to work out the tune, ensure that you are shooting with good form and executing good shots.

Walk back is yet another method to help you guarantee that your bow's centershot is true, meaning your rest is in the proper position left to right. The process is simple: you shoot at a single spot on a target using the same pin at a variety of distances and monitor the results.

First, apply a piece of tape vertically straight up and down (plumb) through the middle of your target. Make sure you have an aiming point that the tape runs through. Then sight in your twenty yard pin to that aiming point. Now, moving back to 30, 40, 50 and 60 yards, aiming and shooting at the same aiming point and using your same 20 yard pin at each distance. If you shoot a single pin slider, do not move your sight. At each distance, use the same 20 yard pin.

A well-tuned rest center shot will yield in a straight vertical line. Every arrow should be vertically in a line in the tape, 20 all the way to 60 yards ( I ). If the line of arrow runs off to the left ( / ), you will need to move your rest to the right. If your arrows run off to the right ( \ ), you’ll need to move your rest to the left.

Make small changes and reshoot as you go. Remember that after you make an adjustment to your rest you will likely have to move your sight and resight in again at 20 yards before starting the walk back process again. Recording your adjustments and results can help you keep things moving in a positive manner. Once again, this may take a few days to make sure you get good shots and results.

For those that have even more time to test and tinker, torque tuning might be worth considering. Torque tuning essentially is adjusting your rest into a position (forward or farther back) so that when your grip is less than perfect (like it regularly is in a hunting situation) your arrow will still fly true.

To start, sight your bow in at 20 yards. Then, draw your bow and slightly torque your grip so that the riser has more pressure to one side or the other (use common sense, do not derail your bow) As you do so, take note of what direction your stabilizer is pointing, then put your pin on the target and fire an arrow.

If the arrow impacts the direction that your stabilizer was pointing when torqued, move your rest farther back and repeat. If the arrow impacts the opposite direction of the way your stabilizer was pointing, then move your rest farther forward and repeat. Overall, you are trying to find the sweet spot where, if you have less than perfect grip and are torquing the bow, the arrow will still impact the desired spot. After you find the spot, test your results by torquing the bow both left and right and shooting to confirm your results. You can also step your yardage back to 30 or even 40 yards and repeat to fine-tune your rest location for maximum forgiveness.

Finally, good broadhead flight is the reason we all started tuning in the first place and, if you’ve done the work with other methods like paper tuning and bare shaft tuning, it should be really close already.

A fixed-blade broadhead is going to have more surface area than your field tips and because of this will exaggerate an error in flight. Before I begin shooting broadheads, there are a few steps I like to take to ensure that any issues I might see are not the issues with the arrow/broadhead and are, indeed, issues with tune.

The first step is to install a broadhead and check for alignment by spinning each arrow. Any misalignment will cause a wobble in the arrow and poor flight. To check each arrow, use an arrow spinner like the Pine Ridge Arrow Inspector. Spin each arrow, taking note of the broadhead tip, watching for any wobble in the tip. Another method that I prefer is to put the tip of the broadhead up against a cardboard box and as you spin the arrow you will see the point start to make a circle in the cardboard if there is any misalignment. Perfect alignment will result in a pin hole in the cardboard and perfect alignment.

If the arrow tip does make a circle in the box, rotate the arrow tip until it’s in the top most position then use a sharpie to mark the arrow tip at that position. Rotate that arrow 180 degrees from that mark and then apply pressure to the point of the head on a hard surface. What you are wanting to do is to bend or push the insert in alignment with the broadhead. Recheck alignment by spinning the arrow and broadhead again. After your arrow/broadhead combos are put together, it’s time to shoot them.

For a detailed look at broadhead tuning, you can check out an article and video I did on this here.

Hopefully, your broadheads fly perfectly and impact along with your field tips out to 80 yards, but sometimes that is not the case. One of the most common questions I get about broadhead flight is how do I get my broadheads to fly with my field tips? Also, what is your broadhead flight telling you about your tune? The first thing I would suggest is that you should not automatically just move your sight so your broadheads are impacting where you want. That is a Band-Aid and you won’t be able to practice with field tips and have them impact where you want. Below, I have included a table to help you get your broadheads and field tips hitting together.

After you make adjustments to your rest to get your field tips and broadheads hitting together, then move your sight to re-sight in your pins. This method will ensure your bow is well-tuned (good paper/bare shaft tune) and your broadheads and field tips hit exactly where you want them to!

Finally, I’ll provide another table below that can help in your tuning efforts and setting your bow to spec.

Hopefully the COVID-19 pandemic will pass quickly and we can all get back to some normalcy and prepare for the fall hunting seasons. While we have some time at home, stay safe, enjoy time with family and put some real effort into having the most well-tuned bow you have ever entered a season with. All the best!