Pair of bear hunting hounds. Photo credit: Lori Jacobs

Photo credit: Lori Jacobs, Vice President of the California Houndsmen for Conservation

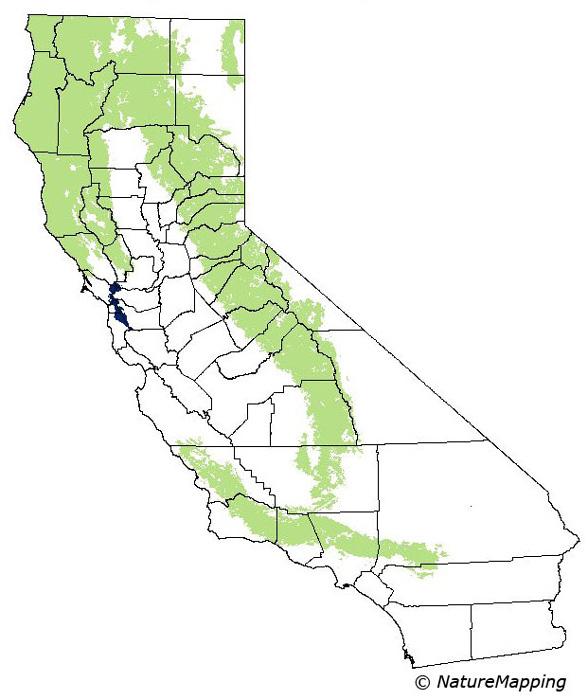

Black bear population range in California. Source: Nature Mapping Foundation

Daniel Richards' Idaho mountain lion. Photo credit: Western Outdoor News

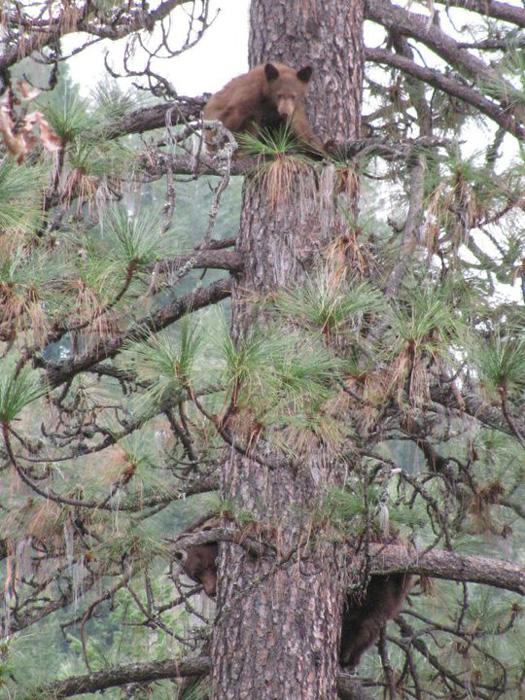

Photo credit: Lori Jacobs

Photo credit: Lori Jacobs

Lori Jacobs with two bear hunting hounds.

If you’ve read my previous article on the legislation surrounding mountain lions in California, some of the following information will sound quite familiar. The similarities of the issues surrounding California SB-1221 and Proposition 117 (the “California Wildlife Protection Act”) are a result of animal rights activist groups and lobbyists removing the decision making power from wildlife management experts and placing it in the hands of politicians and the uninformed general public. SB-1221 was passed in 2012 and made hunting bobcats and bears with hounds illegal in California. Another separate, but similar incident was brought forward recently that California may no longer representing hunters.

In 2012, Governor Jerry Brown signed SB-1221, a bill championed by the Humane Society of the United States (HSUS), that made hunting bears and bobcats with hounds illegal. The basis of this law, according to a HSUS press release is that “Hound hunting is an unnecessary and cruel practice, opposed by 83 percent of Californians, in which dogs are released to chase frightened wild animals often for miles, across all types of habitat.” In addition, ”High‐tech radio devices fitted to the dogs’ collars allow bear and bobcat trophy hunters to follow the pursuit remotely. Dogs pursue their target until the exhausted animal climbs a tree to escape or turns to confront the dog pack. The trophy hunter then arrives on the scene and often shoots the animal off a tree branch at close range.” Note the degree of scientific evidence in this argument. Once again, lobbyists and animal rights activists have circumvented the proven model for conservation in California by appealing to voter empathy or bleeding hearts.

Much effort was made to paint houndsmen as blood thirsty “trophy hunters” who terrorize wildlife for some kind of sick amusement. Opponents even went as far as to say using hounds is not considered “fair chase” and claimed that Montana had outlawed the use of hounds to pursue bears for this very reason. According to Cheri Shankar, “It's an embarrassment to realize that states like Montana, where hunting is widely practiced and even more widely supported, long ago prohibited hounding. How long ago? For the sake of "fair chase," hounding was outlawed there in 1921.”

Isn’t it strange then that Montana still allows the use of hounds to hunt bobcats, mountain lions, and raccoons? Perhaps there are different standards for fair chase of these species? Not likely. In reality, the use of hounds to pursue bears in Montana was outlawed due to the state’s grizzly population. Not only are grizzly bears more carefully managed, they do not tree and, therefore, present a threat to hounds and hunters in pursuit.

Those opposed to hounding claim that using hounds to pursue bears is inhumane both to the dogs and the bears. “It caused harm to the dogs,” says Senator Ted Lieu in an interview with ABC 7. ”Sometimes the dogs would get in fights and get killed. Sometimes they would get injured. It was inhumane to bears and it was unsporting."

“Our efforts are focused on what we consider to be the worst abuses,” says HSUS Wildlife Protection Director Elise Traub in an Outside Online interview. “I think the public and even a lot of ethical hunters have these standards like fair-chase, where animals have a fair chance to get away from the hunter. That’s completely absent in hound hunting, and when the public learns about that, they’re disgusted by it.”

Allowing groups such as the HSUS to determine what is “fair chase” is dangerous.

Again, California has allowed lobbyists to circumvent scientific management practices with emotionally based propaganda. The California Environmental Quality Act is a policy that was established to “ensure that policy decisions impacting our natural resources are based upon the best available science and environmental review,” by the California Fish and Wildlife Commission. The decision to outlaw the use of hounds to manage the bear population was based on no science, only the agenda of the HSUS, whose mission statement includes “to end all hunting.”

Black bear population range in California. Source: Nature Mapping Foundation

Many might be surprised to learn that California is in the top three states for black bear populations. According to the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW), estimations of California’s black bear population are between 30,000 and 35,000.

California black bear population estimates (2000-2015)

In order to manage this population, the CDFW determines the number of bears to be taken each season. Since 2012, the quota has been set at 1,700 bears. This number, based on scientific data, is the maximum amount of bears that can be taken to maintain what experts have declared is a healthy population. The season runs from the last weekend in August to the end of the year or until the quota is met. In 2012, the last year before the hound ban, the quota was met in early December, ending the bear season. In 2013, the first year after the ban on hounds, the season ended at the end of December and only 1,078 bears were taken, representing a 45.1% decrease from the 2012 season. A total of 23,397 bear tags were issued and the hunter success rate was 4.6%, according to the CDFW.

Annual California black bear harvest

The ban on hounding lead to a decrease not only in the hunter success rate, but in the number of hunters buying tags and in the number of hunters specifically pursuing bears. Considering that tag sales are a great source of revenue for conservation and management of wildlife, this is a great loss.

“California's wildlife conservation approach is based on the proven model of management, in which hunters and fishermen pay license fees to fund professional biologists who set seasons, bag limits and methods of hunting,” says Bill Gaines, who is the president of the California Outdoor Heritage Alliance. “The system is deliberately set up to be separate from partisan politics. SB-1221 sets a terrible precedent and demonstrates why wildlife management should not be political. Natural resources, including wildlife, are too important to be pawns.”

Furthermore, according to the California Houndsmen for Conservation (CHC), “hunter-generated funds have proven integral to adequate management of state lands in current times of severe budget deficit, and an estimated 5,700 of the people who buy licenses use hounds to hunt.” With their method of pursuit made illegal, many houndsmen simply elected not to buy a tag. Again, while environmentalist groups raise money to pass legislation against hunting, hunters generate revenue to actually preserve and manage wildlife. When said legislation leads to a decline in revenue generated by sportsmen, both taxpayers and wildlife suffer.

SB-1221 was curiously introduced by Senator Ted Lieu one week after “the Humane Society of the United States posted a photo of the new (and now former) president of the Fish and Game Commission Daniel Richards holding a dead mountain lion he’d shot during an Idaho hunting expedition. Coincidence? There’s been no official statement that the two events are linked, but since it’s illegal to shoot mountain lions in California, Dan Richards’ actions sparked enormous outcry. The powerful HSUS backed Lieu’s bill shortly after the image made its rounds, and started organizing rallies and activating email lists to engage its more than 1.2 million California supporters.”

Evan Heusinkveld, who serves as Sportsman’s Alliance Vice President of Government Affairs, explained that “the California Senate today chose retribution and revenge over sound science-based wildlife management. Despite having a Fish and Game Commission explicitly designed to handle these questions free from the politics of the statehouse, the California Senate voted in favor of a hunting ban.”

The use of hounds had previously been the most effective way of managing California’s expanding population of black bears. Even after the ban, the state employs houndsmen to aid in dispatching or relocating problem animals such as mountain lions and bears in rural areas because it it the most effective method.

Since hounding has been made illegal and the harvest numbers of bears has decreased, problem animals amongst human populations have risen.

CDFW wildlife biologist Vicky Monroe says that “wildlife officials in Central California’s Kern County […] received 1,400 bear calls between June and December of last year. That’s more than the county received in the 20 previous years combined.” HSUS acknowledges the “uptick in the number of human-bear encounters over the past few years, [ but claims] black bear hunting is not effective at reducing conflicts with people.”

Photo credit: Lori Jacobs

They claim that hunters don’t kill the so-called “problem bears” because they are usually hunting in the backcountry. Scientific evidence however shows that an overpopulation of bears in the so-called backcountry will cause bears to seek new territory, which, in the age of human expansion, means that they are moving into our neighborhoods. Since the ban, the number of bears frequenting trash cans and areas of human populations have increased. Though proponents of SB-1221 may argue that hunting has no impact on these bears, the increase since the ban speaks otherwise.

Lori Jacobs, an avid hunter and Vice President of the CHC has been hunting with hounds for more than 30 years and says that “hound hunting is the only type of hunting that is catch and release; you are not always out there to kill. To most houndsmen and women, just being out with the dogs, family and friends, and watching the dogs do what they were bred to do and love is what it is all about. It goes way beyond killing; to be able to get up close and look one of the most magnificent animals in the eye is truly amazing. I would much rather see them in their natural habitat than in a zoo. To most houndsmen it is simply put, ‘It’s not about the thrill of the kill; it’s about the sound of the hound.’” Many houndsmen like Lori feel betrayed by their state government as their heritage and way of live has been criminalized.

Activist groups claim that the hounds are poorly treated, and put in harm's way. Lori disagrees. “Houndsmen take the absolute best care of their dogs,” she says. “They are exercised, fed well, vaccinated regularly and have comfortable living quarters. A hound is one of the truest of athletes there is and for them to perform properly they must be in top condition mentally and physically. You couldn’t expect an emaciated or abused hound to do it’s job!”

“Hounds were bred to hunt and absolutely love it, you do not have to force them. Dogs have been used to hunt since mankind, it is in their heart and soul. They are a part of the family. Given the choice to hunt or be a pet, if the hound could speak they would say, ‘Let me hunt!’”

California’s deer population faces a number of struggles. While habitat fragmentation and human expansion are a leading threat, the unchecked population of predators also poses a real risk to deer populations. With mountain lions on the protected species list, a poorly managed bear population, and the recent migration of wolves into California, ungulate populations are in trouble.

Once again, the HSUS has won a major victory on the road to “ending all hunting” in California. Despite an ever growing black bear population, they have succeeded in circumventing sound management practices and removed the decision making power of specialized wildlife management experts while simultaneously reducing the funds generated for conservation by hunters. While their goal is to “end all hunting,” their method is “death by 1000 cuts.” By systematically attacking small aspects of hunting, they have succeeded in taking away small pieces of heritage from sportsmen. Where will it stop? How can we as sportsmen affect change? The reality is that roughly 10% of voters are anti-hunting and 10% are for it. As sportsmen, it is our duty to portray hunting in a positive light to those in the 80% who may be on the fence. With social media, we all have a platform; be sure to represent your heritage in a manner that is palatable to the general public and support groups that are going to bat for the sportsmen at the statehouse.