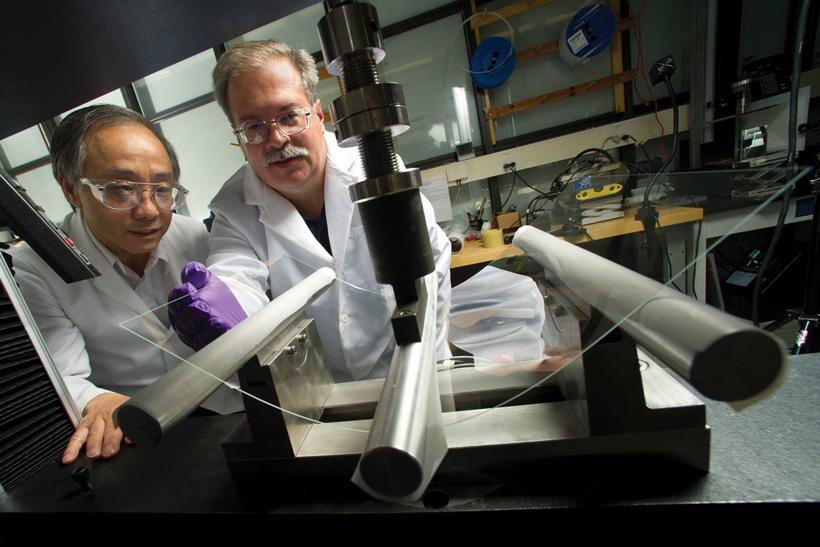

Photo credit: Getty Images

Photo credit: Corning Gorilla Glass

Photo credit: Gizmodo

Photo credit: Bestbinocularsreviews.com

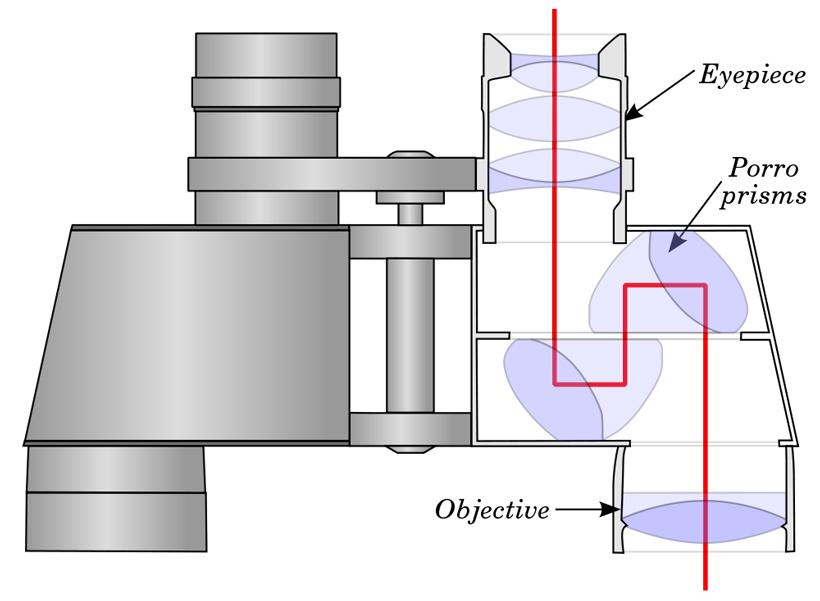

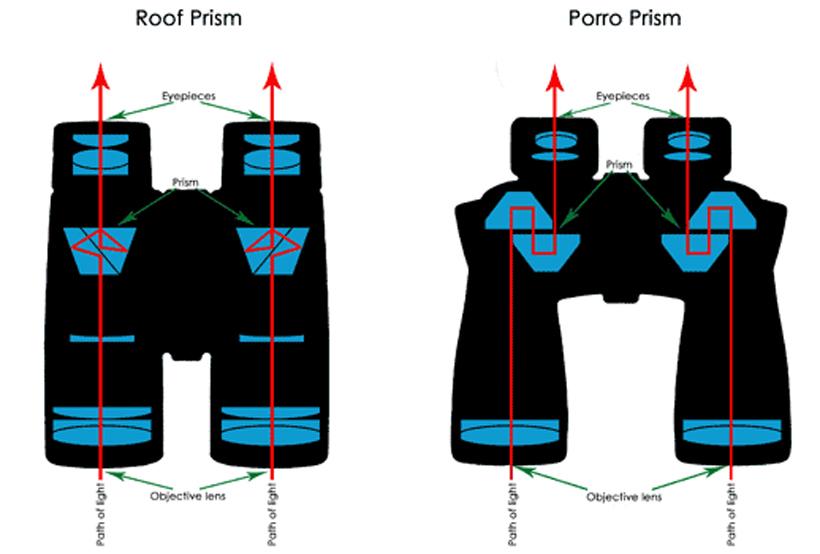

How roof prism and Porro prism binoculars work. Photo credit: Wex Photographic

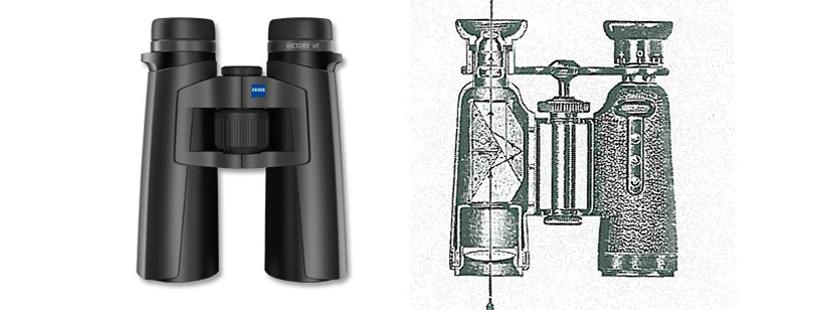

The new Victory HT binoculars next to older Zeiss binoculars. Photo credit: Zeiss Optics

Photo credit: Opticampus.com

The basic technology of optics has mostly remained the same for the past century: light passes through glass and results in magnification. However, design refinements and secret, proprietary glass formulas continue to change and improve hunting optics. With so many choices, how to choose a quality optic becomes daunting for a non-expert. That is why we went out and found the experts for you.

Knowing the science behind the lens will make choosing that next optic a bit easier. You will know what to look for and what to avoid. You may even find you have no reason to upgrade your current setup right now. No matter what, you will never look at glass the same way again.

“Even among quality optics there are lots of different kinds of glass that influence light in different ways,” explains Dr. Bradford Behr, senior optical scientist at Tornado Spectral Systems. Optics makers have millions of glass types to choose from. This wide variety means that glass types can be combined to solve particular problems, such as minimizing chromatic aberration (when the red outline of something doesn’t line up with the blue one, causing the image to spread) or blocking specific lightwave types from getting through.

At its base, glass is mostly silica, the same compound that makes up 59% of the earth’s crust and a common constituent of sand. However, “saying glass is mostly silica is like saying a cake is mostly flour and water,” explains Dr. Behr. “Just flour and water doesn’t make a very interesting cake. It’s the little amounts of spice and flavorings you put in there that differentiates one sort of cake from another. Likewise with glass: you start with silica but you add in little bits of different metals, what you normally would think of as contaminants.” These small additions change how glass refracts light as well as its light dispersion, durability and clarity.

Quality glass must be well-mixed to avoid forming stripes with high and low mineral concentrations or other irregularities in the glass. A mineral band or air bubbles will cause the light to deflect unpredictably. No hunter wants a hazy optic to look at a buck with artistic, soft focus. Consistency and clarity are key, and it starts very early in the glass production process.

ED glass. Perhaps the most important glass type for hunters is ED (Extra low Dispersion) glass. ED glass means low chromatic aberration, giving you a sharper image and more accurate color rendering. ED glass comes standard in most premium binoculars, riflescopes and spotting scopes. It is also one of the reasons for these optics’ premium prices, explains Joel Harris, a passionate hunter from Carl Zeiss Sports Optics.Gorilla glass. Made by Corning, this extremely durable glass makes up the front face of many smartphones and tablets.

The glass itself is a sophisticated, proprietary blend of raw materials which is toughened in a molten salt bath of 400°C (752°F). The end result is scratch resistant and can withstand high impacts. This and similar glass processes are likely to change the future of hunting optics integrated with electronics.Sapphire. There was a lot of talk the past year about Apple using sapphire glass on the next iPhone. Twice as durable as regular glass and about as hard as a diamond, artificial sapphire is also extremely expensive.

The cost comes from the complex process needed to grow the gemstone in impurity-free sheets, then slice it. Although sapphire glass is likely to be found scanners at your grocery’s checkout, in the windows of armored cars and in caustic manufacturing environments, it is unlikely to make it to the hunting field any time soon.

High Definition (HD) is not a type of glass or lens, but a measure of image resolution. In optical terms, HD light transmission “is more than the human brain can distinguish. It’s above and beyond it,” Harris says. As optics have steadily improved, the resulting higher light transmission and resolution only become measurable by spectrometers, not the human eye.

Prisms allow binoculars to stay compact enough to use in the hunting field. Without prisms, binoculars would be long and unwieldily, like a miniature periscope on a submarine. In binoculars prisms perform two functions. The first is to flip the image so it appears right side up. The second is to fold the optical path into a zigzag, making the binocular tubes shorter.

Even though manufacturers could simply use mirrors to create internal reflections, Dr. Behr points out that prisms stay better aligned. Binoculars have lots of different prism arrangements, but the roof prism and Porro prism are most common for hunting binoculars.

Porro prisms are named for the Italian optician Ignazio Porro. He patented this prism setup in 1854. It was later refined by optics makers like the Carl Zeiss company in the 1890s.

“Porro prisms have the added benefit that they use an optics effect called ‘total internal reflection’, where the face of the prism acts like a perfect mirror, so you get a brighter image,” Dr. Behr continues. “The roof prism requires a reflective coating (silver or aluminum usually) which will not reflect quite as well and can tarnish over time.”

However, Porro prism binoculars tend to be larger and wider than roof prism binoculars, which are more compact and portable.

Thankfully, there are incredibly high quality optics available in both styles. Look for prisms made from high density glass, like BAK-4; less expensive BK-7 prisms will have squared-off, non-circular exit pupils, say Michael and Diane Porter on Birdwatching.com.

We have looked at glass and prism types, but the secret for many optics lies in proprietary coatings that go over glass surfaces. Glass manufacturers and optics makers are extremely secretive about both what goes inside their glass and what coats it. What we can do is look at what the process entails and how it affects hunting optics.

Glass coatings work by laying down extremely thin layers of material over the glass. These materials are somewhat like glass (often transparent) but they help with light transmission and scratch-resistance. Magnesium fluoride (MgF2) is a common coating due to its anti-reflective properties. Multiple coating layers take advantage of the fact that light is a wave as well as a particle, amplifying the waves to ultimately create a bigger wave. A bigger light wave means that a larger percentage of light actually gets through the optic instead of going in the wrong direction, which creates a brighter optic. A brighter optic ultimately means you will be more likely to see an animal in low-light conditions.

Conversely, coatings also reduce the glare coming back off the glass through destructive interference, which causes the reflection bouncing off the glass to become as close to a zero wave as possible.

Think of when you look at a lake. Even though most of the sunlight actually goes into the water, enough hits the surface to dazzle or blind you with glare. Light and a glass lens works in the same fashion, but coatings minimize what bounces back. To think of it another way: coatings cause light waves to hit a gentle ramp going both into and out of a piece of glass. Along with glass composition and shape, coatings allow optics engineers to make the light act how they wish both directions.

Coatings also help minimize the light loss that happens when light moves from air to glass. The standard light loss from air to glass is 4%. For example, Zeiss has a riflescope “that has 17 pieces of glass in there. Multiply that by four and see what you’re losing in light transmission,” says Harris. “Typical optical glass has a transmission of 90+%, but since there are many elements in a binocular or riflescope, the total transmission is generally in the 85-90% range.”

Zeiss has recently unveiled a binocular that has 95% light transmission, an incredibly bright optic. These optics stay as bright as they do because the right coatings ease this transmission and can reduce light loss to 1/4% to 1% instead of 4%. The result is a brighter image that is sharper and more comfortable to look at, even if you are glassing an animal over a mile away.

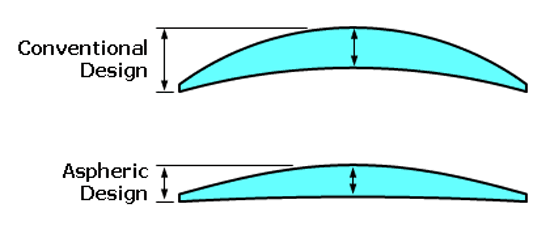

Another innovation besides advanced coating techniques in optics is changing lens shape. A traditional lens is spherically shaped, meaning that if you continued its curve beyond the lens itself you would have a circle. This shape allows the lens to focus light to a single point. Spherical lenses are relatively easy to manufacture but they are not completely perfect for focusing the light.

Photo credit: Opticampus.com

Aspherical optics literally reshape lenses to do a better job of focusing. Modern technology has streamlined this process to the point where you are likely to see aspheric lenses (or aspheres) in Nikon and Canon camera lenses and hunting optics. Computer controlled milling machines can produce these specially shaped lenses much more easily than the labor-intensive hand polishing that traditional lens-making required.

Now, one asphere can focus the light in a certain way instead of an optic requiring three or four standard lenses. The result is lighter optics that are also more durable since there are fewer pieces to potentially shift inside.

A great piece of glass is only as good as its optomechanics, another name for everything holds the lenses of an optic in place. Optomechanics cover all the parts of an optic, including the tube, the casing and the mountings that keep your optics crisp and clear. These are a key part of engineering great optics, says Dr. Behr.

“You need to design the optics and optomechanics together,” he explains. “Taking a holistic approach means making sure that the parts that are holding the glass lenses in place are going to hold them securely without squeezing the glass too much. That, of course, can break the glass.”

Optomechanics also ensure that optics can withstand falling on the floor or a variety of temperatures and still stay in focus. Basically these components keep the glass safe and all the lenses separated by the proper amount so that you can focus the optic. “You can have the most beautiful lens, but if you build poor optomechanics around it, it’s going to perform poorly. It’ll be a V8 engine inside a Pinto.”

Quality components are thus another huge part of the evaluating optics. Better quality carries a higher price tag but will often perform better for longer. Both Dr. Behr and Harris advise trying out a few different optics, whether in the store or in the hunting field, to see how they compare. The optic should feel solid and well-built, not flimsy. Look for optics made with metal and carbon fiber. When looking through, the image should be sharp and bright, not hazy or blurry.